Safeguarding Gut Barrier Function

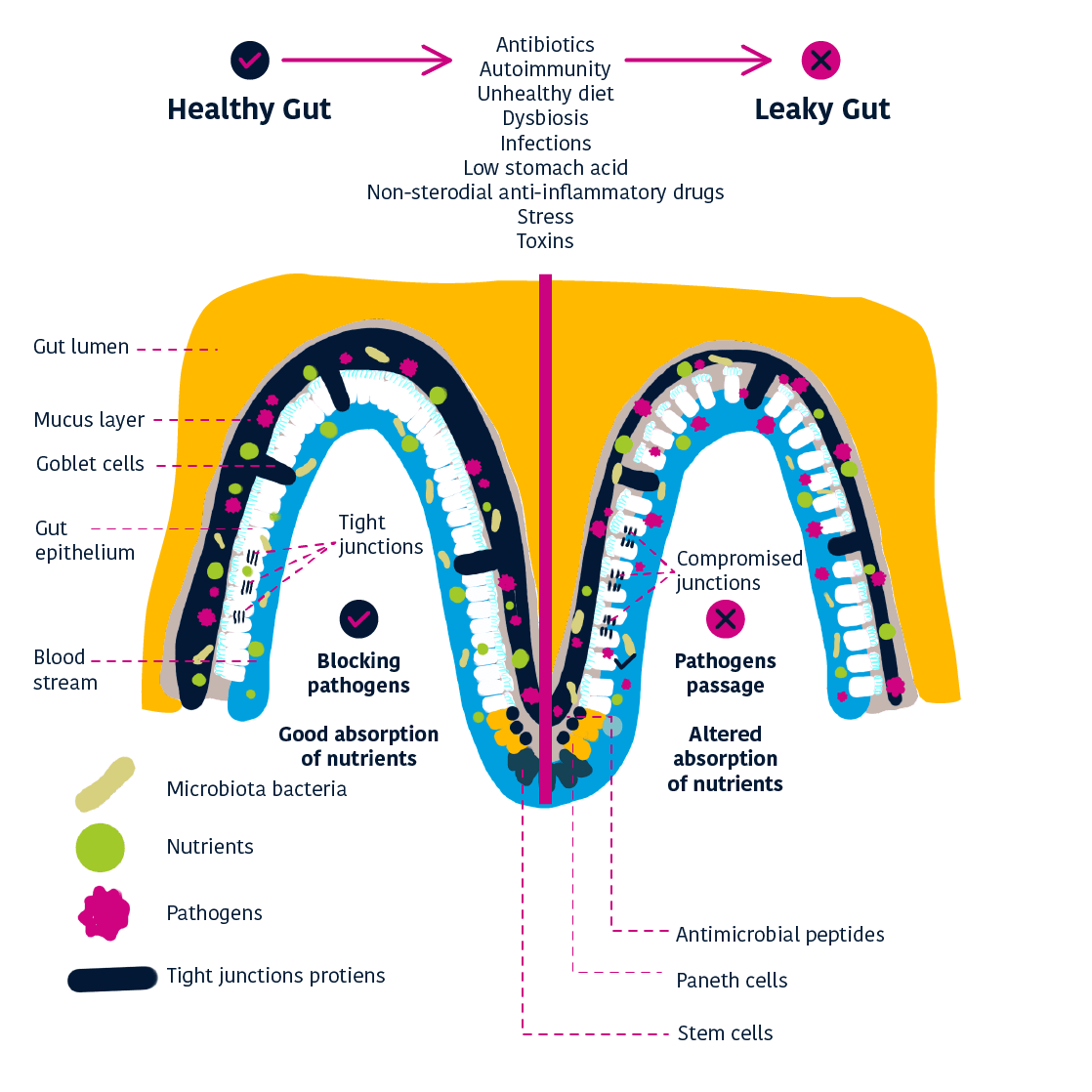

The inside of the gut (the ‘lumen’) is separated from the rest of our body by a single layer of cells called the intestinal epithelium.

This single layer of cells is so important that the body renews it entirely every 3-5 days in order to remove damaged cells. 1 The spaces between the cells are sealed by tight junctions which regulate the permeability of the gut barrier – preventing large molecules from passing through, but allowing in ions, water and small compounds.

However, if the efficiency of the epithelium is compromised, then gut barrier function becomes impaired.

Mucus: protecting the gut barrier

There is a mucus layer covering the intestinal epithelium, produced by ‘goblet cells’ within the gut barrier. 3

This mucus layer is crucial in protecting the gut from physical damage and invasion by microorganisms – so if the thickness of the mucus layer decreases, the effectiveness of the gut barrier is compromised. 3

The mucus layer itself is strengthened by antimicrobial peptides (AMPs.), which help defend against microorganisms by killing or inhibiting the growth of bacteria close to the epithelium. 3

Gut barrier disruption and ‘leaky gut’

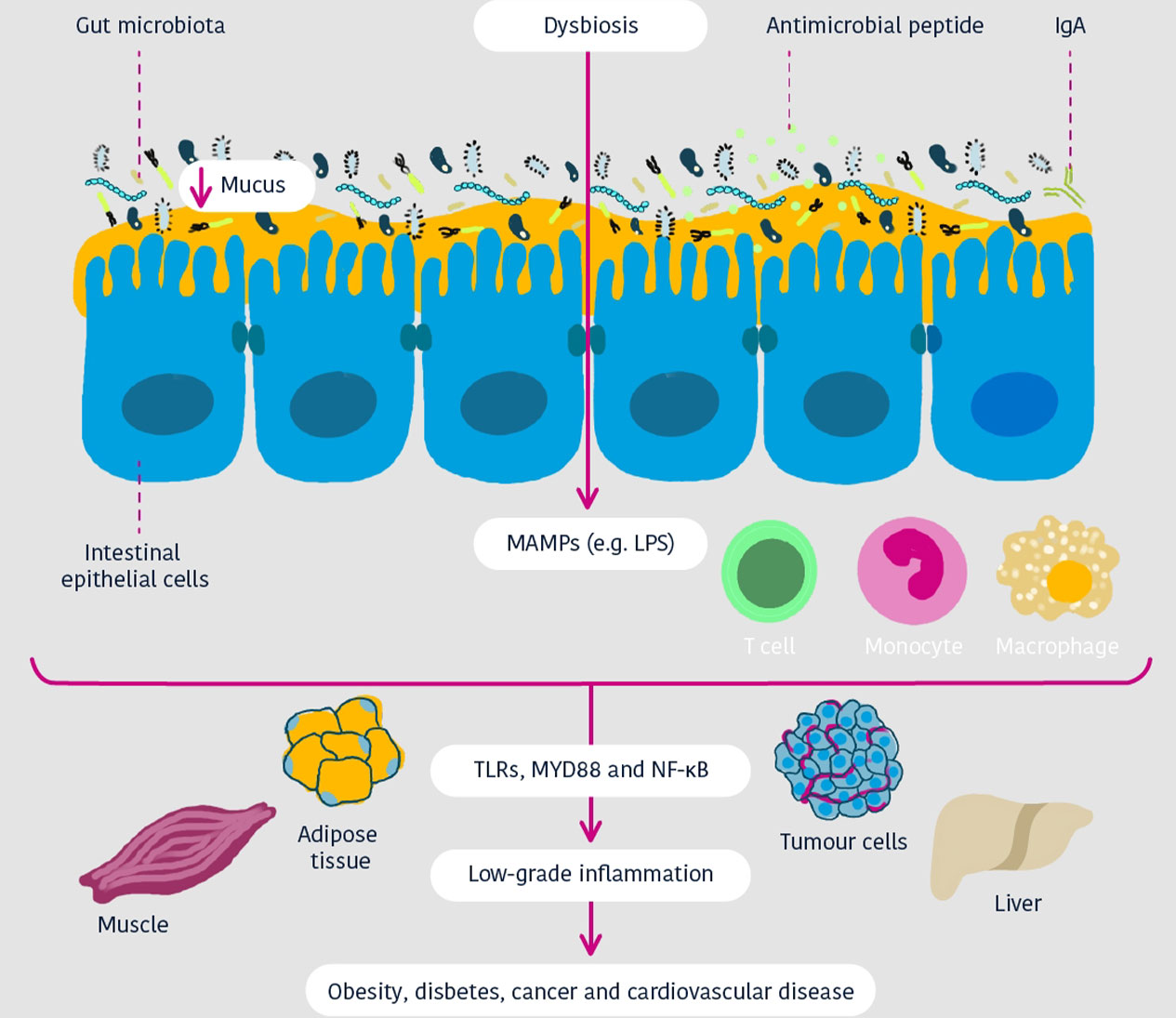

Cani and Jordan Nature Reviews Gastro & Hepatol 2018

The gut barrier manages what comes in and goes out of the gut, and when the function of the gut barrier is disturbed, the gut becomes more permeable – meaning that more components will be able to pass through. 4

A balanced and diverse gut microbiota is needed for the development, maintenance, and optimal function of the gut barrier, but this composition comes under threat when there are changes in diet, stress, antibiotics or diseases. This leads to a disruption of the gut microbiota composition and functions – a disruption referred to as dysbiosis. 4

Dysbiosis could allow gut content such as bacterial metabolites and molecules – as well as bacteria themselves – to leak through the gut barrier and into the rest of the body. This increased epithelial permeability is also known as ‘leaky gut’. 4

How Akkermansia works

The wider effects

of ‘leaky gut’

When gut permeability is increased, pro-inflammatory toxins (for example lipopolysaccharides – LPS) can enter the bloodstream. Finally, it leads to chronic low-grade inflammation (a low-level of inflammation but which lasts a long time) throughout the body (e.g. in the liver and adipose tissues).

‘Leaky gut’ is also associated with a variety of gastrointestinal disorders. They include:

INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE (IBD)

IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME (IBS)

COELIAC DISEASE

EARLY STAGES OF COLON CANCER DEVELOPMENT

The condition is also associated with numerous extra-intestinal disorders 2 & 3 such as:

OBESITY

TYPE-2 AND TYPE-1 DIABETES

NEUROLOGICAL DISORDERS

FOOD ALLERGY

How Akkermansia muciniphila can help repair ‘leaky gut’

Because of Akkermansia muciniphila’s role in the mucus layer – using mucin as its sole source of nutrients – it also acts to promote mucin production.

By consuming mucin, it stimulates the body to continue mucin production, thereby renewing the mucus layer. Maintaining continual mucus production helps keep the human gut healthy by preventing the invasion of pathogenic bacteria.

Furthermore, as Akkermansia muciniphila processes mucin, there are a number of useful byproducts:

Short-chain fatty acids

(e.g. propionate and acetate)

Amino acids

Vitamins

Akkermansia muciniphila makes these byproducts available to the body and other gut bacteria – and because it supplies nutrients in this way, it can be considered a keystone species.

As well as being associated with good gut barrier function, using Akkermansia muciniphila as a food supplement in combination with a healthy and balanced diet has been shown to restore gut barrier function in obese mice. 5

Optimal Akkermansia muciniphila levels have a number of positive effects:

maintaining normal gut permeability

preventing pro-inflammatory toxins from entering the bloodstream

REFERENCES

1 Park, J. H., et al. (2016). “Promotion of Intestinal Epithelial Cell Turnover by Commensal Bacteria: Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids.” PLoS One 11(5): e0156334.

2 Cani PD (2018) Human gut microbiome: hopes, threats and promises. Gut 67 (9):1716-1725 doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316723. Download

3 Paone P, Cani PD (2020) Mucus barrier, mucins and gut microbiota: the expected slimy partners?Gut 69 (12):2232-2243. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322260. Download

4 Martel, J., et al. (2022). “Gut barrier disruption and chronic disease.” Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 33(4): 247-265

5 Plovier, H., et al. (2017). “A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice.” Nat Med 23(1): 107-113.

6 Cani, P. D., et al. (2022). “Akkermansia muciniphila: paradigm for next-generation beneficial microorganisms.” Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 19(10): 625-637.